The youngest of nine boys, I lived peacefully with my family in a neighborhood filled with both Christian and Jewish families. Although antisemitism was present, I didn’t understand its full impact until Hitler came into power. My father was an orthodox Jew and a builder by trade. His faith kept him from emigrating to the United States before the war due to the restrictions our family would have to endure as Jewish Americans.

After Hitler came into power, ghettos were set up in various cities in Germany and Poland. My family was forced to leave our neighborhood homes, and we were led to the Lodz Ghetto, taking only what we could carry. Everything else was lost. My family lived in a small room in the ghetto. Food was scarce and conditions were horrid. When it came time for deportation, I went into hiding for four weeks, living in the connected attics above the apartments. People who knew I was hiding brought me a piece of bread or a potato that allowed me to survive. In order to force me out of hiding, my younger half-brother was held hostage – a strategy used often to get people to cooperate with German authorities.

From the ghetto, I was taken to Nordhausen, an ammunition factory in Germany. Every morning and every evening we were counted. If someone died during the day, the prisoners would have to drag the dead body by the teeth and put him in line. At night, we piled the bodies together and carried them up in the hills to be burned; some were still alive. In this factory, I was wrongly accused of stealing and I experienced a brutal beating by a guard. Forced to march with only rags held on my feet by string, I walked from Nordhausen to Dora, a factory that made bombs, where I took the identity of a non-Jew. There I survived British and American air strikes; once I hid in a large bomb casing to save myself from the live bombs above.

As the war came to an end, the factories were evacuated. The SS men chose 120 men to be taken to a beautiful camp for young, privileged German boys. It was a school to train these children in the Nazi way. We lived 120 people in one room. There was a wood stove for heat for the SS men who kept guard but no heat for us. I believe it was this move that saved my life. The beatings stopped, and we were fed bread, wheat coffee and thin soup. When we went to sleep, all 120 of us embraced each other while standing.

At the end of 1944, the Nazis brought prisoners to Lubeck, Germany a port city, and kept us alive on shore. Many thousands of us sat, huddled in the bitter cold. At night we were chased into abandoned farmhouses, with the promise that a big ship would come. We followed this same routine for many weeks waiting for the ship. The ship finally came. It was an old German luxury ship converted into a troop ship. Twenty thousand people, of all nationalities, from Germany pushed into this ship like herrings. They took us out to the North Sea, back and forth, back and forth. On the top deck they had set up machine guns; they

couldn’t break through the English Navy and American Air Force. Instead of surrendering, they opened up the machine guns on the Air Force, and the ship was bombed in retaliation. Everyone was so undernourished that many did not have energy to swim. I fell into the water with the others and lost consciousness.

The English Navy fished me out of the water. Most of those on the ship drowned or got burned to death. Two soldiers stood with machine guns pointing in my direction while two nurses washed me. I didn’t know what was happening; I hadn’t been washed in years. Soon the soldiers told me in German that I was free; English soldiers had control of the area. I spent a few weeks in the hospital until the war ended on May 5, 1945.

Biography from the

Holocaust, Genocide, and Human Rights Project, Monroe Community College

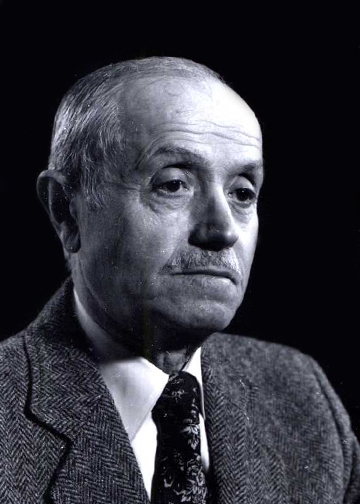

Photograph by Louis Ouzer

-

Shoah Foundation Testimony

-

Shoah Video 1

- Shoah Video 2

- Shoah Video 3

- Shoah Video 4

- Shoah Video 5

- Shoah Video 6

- Shoah Video 7

s

Rochester Holocaust Survivors Archive

Rochester Holocaust Survivors Archive